The 12 Principles of Animation

Last Updated on June 26, 2024 by Ilka Perea Hernández

Whether we draw by hand, with 2D programs, or with complex 3D modeling software, all animation projects follow a set of guidelines known as the 12 Principles of Animation. The right application of these principles will ensure the proper level of expression and movement expected in an animation.

Table of Contents

Historical Context

Once upon a time…

At first, the animations were made with little or no reference to nature. It all started when Walt Disney noticed that the level of animation was quite poor. Out of this concern came a new way of drawing human figures and animals in motion, where the analysis of real action became important for the development of animation.

“When we consider a new project, we really study it… not just the surface idea, but everything about it.” — Walt Disney

From all these exercises and studies emerged new concepts and several techniques, but they were so new that they did not have a name to define them, so it was difficult to explain them to animators. In order to improve communication among them, these new practices adopted their own names, what we know today as The Principles of Animation.

The Principles of Animation

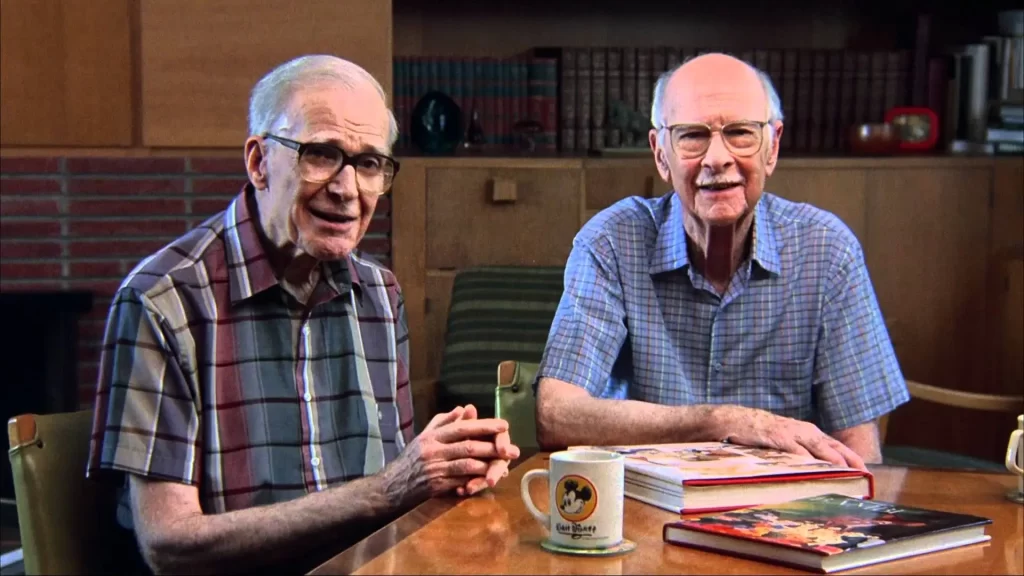

The 12 Principles of Walt Disney Animation are a set of guiding statements released by Disney animators — Ollie Johnston and Frank Thomas — in their book “The illusion of life: Disney Animation”. They represent the starting point for anyone wishing to enter the creative field of animation. Knowing and practicing them will not only help you create animation but will also make your animation alive and meaningful.

Squash and Stretch

Principle of Flexibility

As if they were flexible, the exaggeration and deformation of bodies serve to achieve a more amusing, or more dramatic, effect. For this principle, velocity and inertia, momentum, weight, and mass must be considered.

This principle is useful for the facial and body expressions of characters when you want to emphasize certain emotions and movements.

Anticipation

Prepare your eyes

This principle prepares the viewer for the main action, which is what the character intends to do. Movements should be anticipated to guide the viewer’s gaze and announce what is going to happen.

This technique is divided into three steps:

- anticipation (prepares us for the action)

- the action itself

- the reaction (recovery, ending the action).

Staging

Focus on the Scene

With this principle, we translate the intentions and mood of the scene into specific positions and actions of the characters. By staging the key positions of the characters, we define the nature of the action. There are several staging techniques to tell a story visually. Hiding or revealing the point of interest or creating chain actions (action-reaction) are two examples. Effective use of camera shots and angles helps focus the viewer on the scene. Staging the key positions of the characters will define the nature of the action.

Nikita Melnikov.

The main goal of staging is to tell the viewers exactly where the action will occur, so they don’t miss anything. This means that only one idea occurs at a time, or else the viewers may be looking at the wrong situation. A good example of staging in motion is the eye, which is drawn in one movement in a fixed scene.

Fluid Action vs. Controlled Action

In Straight Ahead Action, we create a continuous action, step by step, until it concludes in an unpredictable action. In Pose to Pose, we break down the movements into structured series of key poses.

Straight Ahead Action gives fluidity to the movement and provides a fresh, loose, and casual look. In Pose-to-Pose action, an initial approach is developed. It is a more controlled animation that is determined by the number of poses, and the intermediate poses. These two techniques can be mixed.

Follow Through and Overlapping Action

Nothing Stops at the Same Time

These two techniques help to enrich and give detail to the action. In Follow Through Action, the character is still moving after the main action. In Overlapping action, multiple movements are mixed, influencing the character’s position.

Virtually nothing stops at the same time. In Follow Through Action, the character is still moving after the main action. In Overlapping action, multiple movements that influence the character’s position are superimposed.

Slow In and Slow Out

Speed Down!

It is about speeding up the center of the action and slowing down the beginning and the end of the action. In the physical world, objects and humans apply momentum before they can reach maximum speed. Similarly, it takes time to slow it down before something can come to a complete stop.

In the physical world, objects and humans apply momentum before they can reach maximum speed. Likewise, it takes time to slow it down before something can come to a complete stop.

A Curved Principle

By using arc lines to animate the character’s movements we will be giving it a more natural appearance, since most living creatures move in curved movements, never in perfectly straight lines.

When a person is shooting an arrow, it barely flies in a straight line. Gravity causes moving objects to arc between the start and endpoints. Even many of the natural motions in the human body move in arcs, such as arms, hands, fingers, etc.

Secondary Action

Depending on the Main One

It consists of small movements that complement the main action and, in fact, are a consequence of it. The secondary action should never be more marked than the main action.

In the physical world, we can observe primary motion only in movement if a person is walking. Secondary actions, such as a person swinging his arms while walking or “birds” ruffling their feathers, help support the primary movements. Even smaller actions, such as eye blinking, are also considered secondary actions. In secondary animation, it is important that it does not detract from the primary animation.

It’s All About Time

Timing gives meaning to the movement. The time it takes for a character to perform an action, or the interruptions and hesitations in the movements define the action. It also helps to give a sense of the weight of the model, and scales or sizes.

This principle also helps to establish the personality of the characters and the emotions they want to express. Timing is used as the main tool to communicate personality through flat shapes that represent body parts.

Exaggeration

Draw Attention to It!

Emphasizing an action usually helps to make it more believable. It involves altering the physical characteristics of a character so that it can capture the audience’s attention.

This principle emphasizes a character’s physical appearance as well as his or her behavior, condition, movements, etc. Basically, it involves altering the physical characteristics of a character so that it can capture the audience’s attention.

Solid Drawing

Recognizable and Three-Dimensional Shapes

Good modeling and a solid skeleton system (or solid drawing as they used to say in the 1930s) will help bring the character to life. It means that the animator must be skilled in understanding three-dimensional shapes in terms of weight, balance, light, and shadow.

Character poses should be clear and expressive with easily recognizable silhouettes. It means drawing your image in such a way that it looks alive, considering its center of balance and weight distribution.

Appeal

Connect with Your Audience

It is about providing an emotional connection with the viewer. The character’s way of being must be coherent with the way he or she moves.

An attractive character is not always pretty. Even an ugly or evil character with a certain level of charisma can gain the viewer’s empathy if their appearance matches their personality. The character’s looks should be consistent with the way they move.

Summary

- The Twelve Principles of Walt Disney Animation is a set of guiding statements released by Disney animators — Ollie Johnston and Frank Thomas — in their book “The Illusion of Life: Disney Animation”.

- The principles are Squash and Stretch, Anticipation, Staging, Straight Ahead Action and Pose to Pose, Follow-Through and Overlapping Action, Slow In and Slow Out, Arcs, Secondary Action, Timing, Exaggeration, Solid Drawing, and Appeal.

Some Insights

The 12 principles of animation are the foundation upon which well-executed animation projects rest. These principles are not rigid rules to be followed but proven theoretical tools.

Together with the basic concepts of animation, constant practice, and a creative attitude, the animator can achieve an artistic style. These characteristics, combined with the application of these principles, will undoubtedly result in a unique, innovative, and distinctive product that will be appreciated by the viewers.

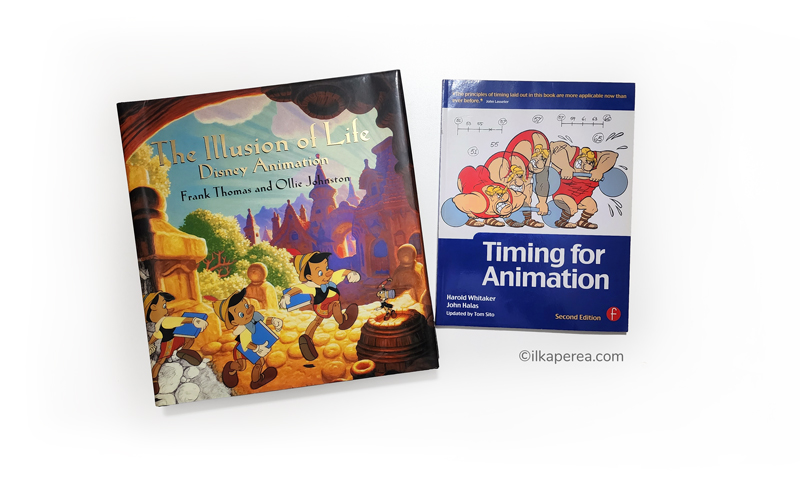

Some Literature

For those designers eager to delve deeper into this dynamic field, I would like to recommend two essential books that stand out as indispensable guides:

- The Illusion of Life: Disney Animation by Ollie Johnston and Frank Thomas

- Timing for Animation by Harold Whitaker and John Halas.

“The Illusion of Life: Disney Animation” by Ollie Johnston and Frank Thomas

First published in 1981, “The Illusion of Life” remains a timeless masterpiece in the realm of animation literature. Authored by two of Disney’s legendary Nine Old Men, Ollie Johnston and Frank Thomas, this book offers a profound exploration into the principles and techniques that have defined Disney’s animation legacy.

“Timing for Animation” by Harold Whitaker and John Halas

In the realm of animation, timing is everything. For designers seeking to hone their craft in this essential aspect of the animation process, “Timing for Animation” by Harold Whitaker and John Halas is an indispensable resource.

Originally published in 1981 and now in its fourth edition, this definitive guide offers a detailed examination of the principles of timing and motion in animation. Drawing from their extensive experience in the industry, Whitaker and Halas provide practical advice and techniques for achieving effective timing in animated sequences.

Any Thoughts?

In the comments section, tell me if you already knew these principles. As a designer, have you done any animation projects, and what has your experience been like? Which book do you recommend learning about animation?

Share

Spread the love… and this post!

If you liked it, share this post on your social networks. Smart designers share good things with others.

Bibliography

- Gyncild, B.; Fridsma, L. (2018). Adobe After Effects CC Classroom in a Book. Adobe Press.

- Jackson, C. (2017). After Effects for Designers: Graphic and Interactive Design in Motion. Routledge.

- Johnston, O.; Thomas, F. (1995). The Illusion of Life: Disney Animation. Disney Editions.

- Shaw, A. (2016). Design for Motion. Fundamentals and Techniques of Motion Design. Focal Press.

- Whitaker, H.; Halas, J.; Sito, T. (2009). Timing for Animation. Focal Press